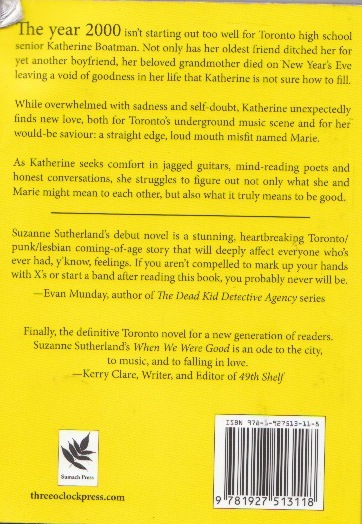

- When We Were Good

- Suzanne Sutherland

- (Three O’Clock Press)

- Toronto, ON

- 227 pp., perfect bound

- ::web/words::

From the out of step heart and head of Annelise Dowd:

Stand in any busy hallway, whether it’s comprised of doctors or students or the recently bereaved, and you’re guaranteed to hear a word so many times its one syllable no longer makes sense. A word so overused and meaningless that it feels gaseous and light between your teeth because it constantly occupies space there. This word is “good.” But what truly entails being “good”? The clean and hollow euphoria of puritanical ethics? Or simply, to feel “good” within oneself? During teenage-hood, as the main character of Suzanne Sutherland’s excellent When We Were Good attests, it’s difficult to feel anything but “lying-in-my-room-alone-with-a-CD-on-good.”

Sutherland’s decidedly queer/feminist YA novel follows Katherine Boatman, a sixteen-year-old Torontonian grappling with depression in the wake of familial loss. A disillusioned Katherine parts through grief’s thick fog to find a mysterious straight edge punk named Marie and a place where lyrics are poetry, X’s on hands are religious iconography, and punk shows can shake one’s innermost being with spiritual fervor. The strictly punk soundtrack (think Jawbreaker, Sonic Youth, and Minor Threat references) Marie introduces is raw and visceral, mirroring the electricity of teenagehood’s first touches, heartbreaks, and unbridled rage.

When We Were Good doesn’t eschew teenage romance and bildungsroman narratives, but instead employs them through the lens of queerness and mental health, transforming them into something new and gleaming and important. With every mixtape exchanged Katherine’s relationship with Marie moves through mild fascination, to steadfast friendship, to love. Katherine finds that if to be “good” is to be at home, then home is not found between the words of any straight edge rulebook, but instead lies within the recesses of the identity she accepts herself. And it is here where Sutherland transfigures the classic Salinger “Who am I?” for a more timely and significant sentiment: “How can I figure out who I am and be okay if everyone is calling me a slut and a dyke?”

Du coeur et de la tête déconnectés de Annelise Dowd: (Des pensées quasi-francophones de Kevin Godbout)

Tenez-vous au milieu d’un couloir occupé, que vous y voyiez des docteurs ou des étudiants ou des récemment endeuillés, vous êtes garanti d’entendre un mot tellement souvent que sa seule syllabe perd tout son sens. Un mot tellement surutilisé et dépourvu de sens qu’il ressemble à une forme gazeuse et légère entre vos dents, car il occupe toujours un espace dans votre bouche. Ce mot est «bon» (good). Mais qu’entend-on par être «bon»? L’euphorie nette et vide d’une éthique puritaine? Ou tout simplement, de se sentir «bon» soi-même? Durant les tristes moments de l’adolescence, comme le dit le personnage principal de l’excellent roman When We Were Good de Suzanne Sutherland, il est difficile de se sentir autre que «à-terre-dans-ma-chambre-seul-avec-un-CD-bon» (lying-in-my-room-alone-with-a-CD-on-good).

Ce roman pour jeunes adultes, aux tons décidément féministes/queer de Sutherland, suit Katherine Boatman, une adolescente de seize ans de Toronto aux prises avec une dépression à la suite d’un deuil familial. Désillusionée, elle diffuse l’épais brouillard de sa tristesse pour trouver une punk mystérieuse nommée Marie, et un endroit où les paroles de chansons sont des poèmes, des «X» sur les mains sont des icônes religieux, et des concerts punk peuvent secouer l’être intérieur de tous avec une ferveur spirituelle. La bande sonore strictement punk (il faut penser aux groupes Jawbreaker, Sonic Youth, and Minor Threat) introduite par Marie est brute et viscérale, en plus de refléter les premiers contacts électriques de l’adolescence, les coeurs brisés et la rage pure.

When We Were Good ne rejète pas l’amour entre des ados, ni la narrative d’un bildungsroman, mais utilise ces éléments perçus à travers la lentille d’une réalité queer et de problèmes de santé mentale. Cet état les transforme en quelque chose de nouveau, étincelant et important. Avec chaque mixtape qu’ils s’échangent, la relation de Katherine envers Marie évolue de la fascination, vers une grande amitié, et même jusqu’à l’amour. Katherine réalise que si pour être «bon» il faut être chez soi, alors ce chez-soi ne se trouve pas dans un livre de règles, mais existe plutôt à l’intérieur des cavités de l’identité qu’elle accepte elle-même. Et c’est ici que Sutherland transfigure le «qui suis-je» (Who am I) de Salinger pour un sentiment plus contemporain et significatif: «Comment vais-je découvrir qui je suis et l’accepter si tout le monde m’appelle une pute et une gouine?»